Sie erwähnte nicht anderes als das reine Vergnügen an unserem Wiedersehen nach so langer Zeit und die Freude darüber, allen Verboten zum Trotz gemeinsam zu genießen, was die Jahreszeit an Schönem bot. Giorgio Bassani, 1962

Für zwei Tage habe ich mir einen Fiat Panda geliehen. Es ist gleich ganz italienisch: Die Frau von der Autovermietung ist supernett und wir erzählen uns Geschichten von Fiat Pandas (dass ich meinen roten Panda vor ein paar Jahren verschenkt habe wollte sie mir erst nicht glauben) während der Computer immer wieder abstürzt. Aber auch das bekommt man hin, indem man in langsamster Schönschrift alle Informationen in eine Kladde schreibt. Irgendwann habe ich den Autoschlüssel und die unnachahmliche Wegbeschreibung zum Parkhaus: "Hinter dem Lamborghini-Stand links."

Sicherlich einer der ungewöhnlicheren Orte der Welt. Das war eine Fabrik zum Trocknen von Tabak (ex-seccatoi del tabacco), der hier früher angebaut wurde. Deshalb außen schwarz, das fängt die Sonne besser ein. Heute ist es ein Museum des italinischen Maler-Bildhauers (hauptsächlich Malers) Burri. Da alle bei Epifania sind bin ich drinnen alleine. https://fondazioneburri.org/la-fondazione/ex-seccatoi-del-tabacco/

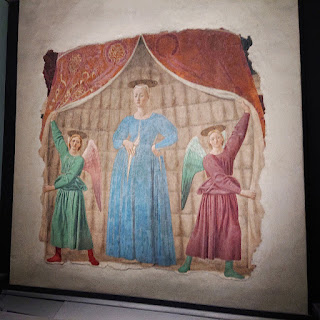

The best picture in the world is painted in fresco on the wall of a room in the town hall. Some unwittingly beneficent vandal had it covered, some time after it was painted, with a thick layer of plaster, under which it lay hidden for a century or two, to be revealed at last in a state of preservation remarkably perfect for a fresco of its date. Thanks to the vandals, the visitor who now enters the Palazzo dei Conservatori at Borgo San Sepolcro finds the stupendous Resurrection almost as Piero della Francesca left it. Its clear, yet subtly sober colours shine out from the wall with scarcely impaired freshness. Damp has blotted out nothing of the design, nor dirt obscured it. We need no imagination to help us figure forth its beauty; it stands there before us in entire and actual splendour, the greatest picture in the world.

The greatest picture in the world…. You smile. The expression is ludicrous, of course. Nothing is more futile than the occupation of those connoisseurs who spend their time compiling first and second elevens of the world’s best painters, eights and fours of musicians, fifteens of poets, all-star troupes of architects and so on. Nothing is so futile because there are a great many kinds of merit and an infinite variety of human beings. Is Fra Angelico a better artist than Rubens? Such questions, you insist, are meaningless. It is all a matter of personal taste. And up to a point this is true. But there does exist, none the less, an absolute standard of artistic merit. And it is a standard which is in the last resort a moral one. Whether a work of art is good or bad depends entirely on the quality of the character which expresses itself in the work. Not that all virtuous men are good artists, nor all artists conventionally virtuous. Longfellow was a bad poet, while Beethoven’s dealings with his publishers were frankly dishonourable. But one can be dishonourable towards one’s publishers and yet preserve the kind of virtue that is necessary to a good artist. That virtue is the virtue of integrity, of honesty towards oneself. Bad art is of two sorts: that which is merely dull, stupid and incompetent, the negatively bad; and the positively bad, which is a lie and a sham. Very often the lie is so well told that almost every one is taken in by it – for a time. In the end, however, lies are always found out. Fashion changes, the public learns to look with a different focus and, where a little while ago it saw an admirable work which actually moved its emotions, it now sees a sham. In the history of the arts we find innumerable shams of this kind, once taken as genuine, now seen to be false. The very names of most of them are now forgotten. Still, a dim rumour that Ossian once was read, that Bulwer was thought a great novelist and “Festus” Bailey a mighty poet still faintly reverberates. Their counterparts are busily earning praise and money at the present day. I often wonder if I am one of them. It is impossible to know. For one can be an artistic swindler without meaning to cheat and in the teeth of the most ardent desire to be honest.

Sometimes the charlatan is also a first-rate man of genius and then you have such strange artists as Wagner and Bernini, who can turn what is false and theatrical into something almost sublime.

That it is difficult to tell the genuine from the sham is proved by the fact that enormous numbers of people have made mistakes and continue to make them. Genuineness, as I have said, always triumphs in the long run. But at any given moment the majority of people, if they do not actually prefer the sham to the real, at least like it as much, paying an indiscriminate homage to both.

And now, after this little digression, we can return to San Sepolcro and the greatest picture in the world. Great it is, absolutely great, because the man who painted it was genuinely noble as well as talented. And to me personally the most moving of pictures, because its author possessed almost more than any other painter those qualities of character which I most admire and because his purely aesthetic preoccupations are of a kind which I am by nature best fitted to understand. A natural, spontaneous and unpretentious grandeur – this is the leading quality of all Piero’s work. He is majestic without being at all strained, theatrical or hysterical – as Handel is majestic, not as Wagner. He achieves grandeur naturally with every gesture he makes, never consciously strains after it. Like Alberti, with whose architecture, as I hope to show, his painting has certain affinities, Piero seems to have been inspired by what I may call the religion of Plutarch’s Lives – which is not Christianity, but a worship of what is admirable in man. Even his technically religious pictures are paeans in praise of human dignity. And he is everywhere intellectual.

Aldous Huxley (1925), “The Best Picture”, in Along the Road, Notes and Essays of a Tourist.